Chris Ratcliff visits the factory in Goodwood to learn more about how this luxury brand remains true to its roots while embracing modern technology.

If you have £300k+ to spend on a car, there's a wealth of choice. Take your pick from Ferrari, Mercedes, Porsche, Koennigsegg, Noble and many others. The one thing that you will notice, though, is how all the cars I've just listed are supercars. Designed to pin you in your seat, deliver mega laptimes around a circuit, and twang knicker elastic when parked outside of any elite hotel or bar.

However, if you don't have a desire to release your inner Villeneuve, but instead want a car to transport you comfortably from A to B, what do you choose? The Ferrari FF is too sporty, the Bentley Continental GT is too common these days (blame the footballers), and the Maybach is discontinued. This leaves you at the gates of the Goodwood Estate, the home of Rolls Royce.

It's hard to define quite why I like Rolls Royce so much. In a way, they eschew everything that other car brands embrace. There is no racing Rolls Royce, they've never hired N-Dubz to lead an advertising campaign, or launched a Nurburgring edition car. Instead, they completely focus on their own niche. Customers often choose a Rolls Royce instead of buying a jet, or a yacht. A Rolls Royce is not a car to drive up and down the Stelvio Pass, but rather a way to travel in absolute comfort and discreet style.

In a way, it has much in common with the tailors of Savile Row, or the finest Swiss watchmakers. Examining a Rolls Royce closely gives you a chance to pick out and enjoy the tiny details. From a distance you only see the trademark grill, the Spirit of Ecstasy figure above the radiator, and the large wheels which classically define the body height. But move closer, and you start to notice increasingly smaller details: the RR initials etched into the headlights, the art deco lights for the rear passengers, the organ pull controllers for the heating vents. The Phantom Aviator concept currently sitting in the lobby of the Rolls Royce factory takes this attention to detail a step further, with design details brought in from vintage aircraft subtly dotted around the cabin and influencing the exterior finish.

I suppose it's what motor manufacturers call 'surprise and delight', the constant uncovering of little details and touches which, well, surprises and delights. I love these details, the little touches and customisations. The regular Phantom starts around £350,000, but they have been customised up to over a million pounds (solid 24 carat gold Spirit of Ecstasy? Yours for £50k), and I can easily see why. Poring over the Aviator concept, I’m struck by the aero-influenced dials and the pressed strakes running along the transmission tunnel.

Both before and after I saw the Wraith unveiled, I spoke to Drive Cult editor Martin and he kept asking me what it was that made me so interested in Rolls Royce, since he couldn’t really see the attraction. I should point out here that I adore the engineering and artistry that goes into a Pagani, or the single-minded attention to detail of McLaren’s road cars. However, to me the draw of a Rolls Royce is in its desire to be completely the opposite. There’s a certain appeal given its heritage – despite its German owners, the brand remains as quintessentially British as Fortnum & Mason, cricket, WI cake sales and the last night of the Proms – but the real draw is how much work goes into their goal of making one the most luxurious, relaxing cars to travel in. Traditional supercar materials like carbon fibre are substituted with carefully chosen maple veneers instead, but the detail in design is just as compelling. To combine matchless upholstery and joinery craftsmanship into a modern production car made of extruded aluminium, while still maintaining a strong feeling of the brand is very impressive.

It’s hard to believe that Rolls Royce have been based at Goodwood and producing the Phantom for only ten years, but the whole range has built upon the resurgence of the brand since the sale by Vickers of the car company to BMW, and the move of production from Crewe to Goodwood. This rejuvenation could have easily lurched somewhere between parody and badge engineering, but the more you drink in a Phantom or Ghost, getting closer and admiring the smaller touches, it never becomes either overblown or commonplace.

The styling of the cars and build of the interiors has continually fused contemporary car design with classic Rolls Royce touches. Crisp, clear black printing on white dials for the gauges vie with a head-up display for driver attention, while the BMW iDrive controller is surrounded with art deco-inspired glass control buttons. From behind the wheel, or better still from the back seat, it’s hard to think of a place I’d rather be when the goal is to arrive at your destination as fresh as when you stepped in the car.

The factory

Upon arrival, the Rolls Royce factory is not what one would expect. It’s neither heavy industry nor a relic of the car industry in times past, with men in white coats tinkering with cars. In order to preserve the nature of the surrounding estate, the ground that was moved to make space for the buildings was formed into banks surrounding the site so that very little of the factory is actually visible from outside. Nicholas Grimshaw, who is well known for being the architect behind the Eden Project, designed the factory itself. There’s lots of glass, wood and aluminium pieces used in automated blinds, and special turf laid over the roof which both works as an insulator, helping the building blend into the surrounds further, and as a nesting area for local wildlife. Inside, large circular skylights are supported by columns which branch out like trees, providing plenty of light inside.

Skylights and tree-like supports [Photo: Chris Ratcliff]

The two production lines, one each for the Phantom and the Ghost, are arranged in the main L-shaped production hall. It’s interesting to see how the slow, low pressure build environment still shows flashes of the BMW Group. A car is being hand-built in one station, with RR-monogrammed mats covering the precious paintwork, while alongside the station are purple BMW branded boxes containing parts from suppliers in custom-made packaging to increase efficiency and reduce waste. However, under one of the raised walkways in the production hall sit a number of trolleys with more of these purple boxes, all packed with nuts, bolts and fixings. I don’t imagine the BMW 3 Series production line allows time for staff to go and collect extra parts as they need them!

A typical Rolls Royce build starts when the bodies and panels arrive at the Goodwood factory from a plant in Bavaria. The first step is the paint shop, where each aluminium body gets a hand-sprayed coat of primer to ensure it reaches and protects all the places an automated spray robot can't reach. Then the colour is mixed. This may be a standard Rolls Royce colour, or a specific shade matched from fabric, a watch, a piece of jewellery, or even a family pet. The colour coat is then sprayed by robot to ensure an absolutely consistent and even coating. Two top clear coats are then applied, before the body is polished for four hours to ensure a deep, lustrous shine.

You can specify your Rolls Royce with a pinstripe, or two, or indeed as many as you wish. These are painted by hand, by one member of staff. If he's off sick, no pinstripes will be completed that day. He uses brushes with a specific mix of squirrel and badger hair, and paints them freehand. No masks, guides or anything else. When one customer asked for their car to have pinstriping added, rather than shipping the car back from the Middle East, the painter packed up his brushes and flew out to the owner. He’s tried to train an apprentice on a number of occasions but no-one has yet been able to achieve the required standard. Where did Rolls Royce find this particular brush wizard? He was a sign writer in a nearby village…

One the paintwork is complete, the chassis is lowered onto the appropriate production line - one each for the Phantom and the Ghost - before doors, bonnet and boot lid are removed and placed on their own special dollies. The striking thing about the production lines is how quiet they are. Each chassis is mounted on a trolley and pushed from station to station, with the majority of tasks being achieved using hand tools rather than pneumatic guns and the like. A single computer at each station outlines certain parameters for the next car, and is used to capture certain details such as what torque a bolt is tightened to in order to maintain a full audit log of each car's build. Once the task is complete and the station in front is clear, the body is wheeled onwards to the next task in its build. To help prevent hold-ups if there's a problem, and to help staff develop, employees are cross-trained on the tasks at different stations rather than just a single task. If there's a problem, anyone knows they can call on other members of the Rolls Royce family to help out and keep the production line moving.

Phantom on the production line [Photo: Rolls Royce]

While the cars progress, drivetrains are built up on rigs in advance to be married to bodies at the right moment, huge brake assemblies lie in wait to be fitted and leather and wood shops prepare the parts that the owners will regularly notice and enjoy, and may have spent many hours choosing and designing with help from Rolls Royce. The leather hides come from herds kept at higher altitudes and without barbed wire fences keeping them in. The altitude eliminates mosquito bites which, along with the barbed wire, can cause marks and damage in the hides. They are then tanned by a single father and son business in Northern Germany who can achieve the extremely high quality desired by Rolls Royce. The hides are then laid out on a cutting table before being cut by a computer controlled scalpel - which gives a better finish than a laser cutter - to make the relevant pieces. Amazingly, ten hides are needed per Phantom, but these come from bulls and are a byproduct of the food industry rather than killed just for the leather. They are then sewed, embroidered, finished and made ready for the car.

Precise laying out of leather hides with laser guides [Photo: Rolls Royce]

The wood shop is a similar experience, with owners' preferences and desires made real from carefully chosen veneers. Standard options include inlaid RR monograms or an outline of the Spirit of Ecstasy, but virtually anything a customer can imagine can be accommodated. Interestingly, certain pieces like the dash are not made from solid wood as you may expect, but rather from many layers of wood and aluminium laminated together for strength. This also prevents wooden pieces splintering in the event of a crash.

Wood shop craftsmanship on display [Photo: Chris Ratcliff]

Several examples of woodworking skill are on display outside the wood shop, showing intricate inlays and incredibly precise carpentry skills. Our guide points out that most are made by apprentices during their learning time with the company. When Rolls Royce first set up shop on the Goodwood estate they had 350 staff, and some members of the wood shop had come from the nearby boat building industry. Now, they've expanded to around 1400 staff and to keep up the relevant skills they need, the specialist areas within the factory like the wood shop have ongoing multi-year apprentice schemes so young people can join the company and become skilled in a specific area, and as a result then become a part of the Rolls Royce family on a full-time basis.

As I’m shown around the factory, certain words keep coming up, while others are conspicuous by their absence. One word that crops up a great deal is technology. As each station in the build process is computerised, each task can be completed, checks and tests performed, and an audit log built up. Should a car suffer a mechanical fault, Rolls Royce can check when that part was fitted, who fitted it, and which batch it came from the supplier in. This is a process you would find at the similarly-named but entirely separate Rolls Royce aerospace factory. In the cars the technology continues, with the new Wraith featuring a gearbox linked to the GPS system in order to anticipate what’s ahead on the road. There’s also an iPhone app which you can use to send Google destinations to the navigation system, amongst other things. However, both in the cars and in the factory, technology is never the focus of the experience, but more a way of discreetly helping matters along.

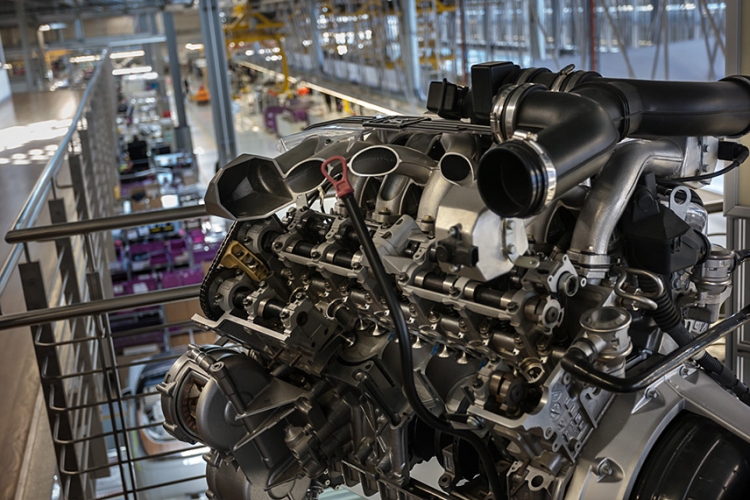

Speaking of technology, I can’t miss this opportunity to talk about the engine. It’s twelve cylinders of high capacity, low stress, classically Rolls Royce power. If ever the relationship between technology and the driver was clearly defined in the Rolls Royce brand, it was in the decision to remove the tachometer, and replace it with a ‘power reserve’ meter instead. Sitting down with the CEO Torsten Müller-Ötvös last summer at the Goodwood Festival of Speed, he highlighted just how central the V12 was to the character of a Rolls Royce, rather than pushing for turbocharged V8s or hybrids – unless governments start mandating them or if major cities become pollution-free zones. This is not idle talk, either; in 2011, Rolls Royce produced the 102EX – or the electric Phantom to you and me – as a test bed to see how feasible such a car is, and to canvass feedback from owners. For now, though, a 6.75-litre V12 provides the power, and a vast cutaway example sits high above the factory floor. Taking a cue from the boat industry, the Phantom actually has two batteries; one for the engine, and the other a ‘leisure’ battery. This is to ensure no matter how much TV you watch, and how chilled your champagne remains, the engine will always start. As a result, the two alternators have to be water-cooled to ensure they don’t overheat.

Cutaway Rolls Royce V12 [Photo: Chris Ratcliff]

Once the cars have reached the end of the production line, they go through a series of test rooms; a full ECU and suspension geometry check, a four-post rig shaker test to ensure the car is suitably quiet for the occupants, a full speed run on a rolling road, and finally half an hour under simulated levels of rain including tilting the car to ensure the occupants will remain dry no matter what Mother Nature may throw at them. Then it’s onto a 15km test drive to ensure everything is as it should be, then a final full valet, including a full check under UV lights to ensure the finish is as high quality as the owners expect.

While technology and family are both words that are mentioned during my tour of the factory, one word I don’t really hear is BMW. It’s often said that a Ghost is ‘just’ a BMW 7-Series with a posh interior, but on the floor at Goodwood you realise that Rolls Royce is an entity in its own right. There’s little sign of any real corporate intervention from Germany, and instead every detail and level of the factory feels very consistently Rolls Royce, right down to the communal canteen where management have lunch alongside the staff from the production floor. There’s also talk of generational employment, where children follow parents into skilled crafts within Rolls Royce. Remember the pinstripe painter struggling to find an apprentice? Apparently every night he goes home, where a 16 year old is practising, waiting to be old enough to apply to join his Dad at the factory.